文章 > 闵冬潮,Mai Corlin:Another China – other inequalities

闵冬潮,Mai Corlin:Another China – other inequalities

作者: 来源:作者赐稿 发布时间:2013-03-11 10:16:26 阅读:

2013年1月,奥尔胡斯大学(丹麦)的博士生Mai Corlin对正在哥本哈根大学访问的闵冬潮教授进行了一次访谈。在这篇访谈稿中,闵冬潮教授从历史处境、现实生活入手,对80年代中国妇女/性别研究所走过的道路进行了评述与反思。着重讨论了自90年代之后性别不平等问题与中国社会发展的联系,并且回答了Mai对全球化时代全球与地方关系的问题。最后闵冬潮教授表达了对当前青年一代对性别不平等激进反抗行动的关注,并期望新一代的实践行动会带来整个社会对性别不平等问题的关注。

Gender inequality is not simply the unfair treatment of men and women. It is a complex issue tied to a whole range of disparities in society at large, argues Professor Min Dongchao, who has just been awarded a Marie Curie International Incoming Fellowship and will be a guest professor at the Nordic Institute of Asian Studies for the next few years. Her object of study is the travels of gender theory between the Nordic countries and China.

Just another day at the factory

Professor Min Dongchao

Like many other researchers and academics of her generation, Professor Min Dongchao was young during the turbulent years of the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976). Most of China’s schools and universities were closed down during that period, and the youth were sent to the countryside or to factories to learn from the working class. Professor Min spent the Cultural Revolution as a worker at the Tianjin Machinery and Tool Factory, beginning her factory career at the age of 15 in 1969 and staying there for eight years.

Professor Min Dongchao

Like many other researchers and academics of her generation, Professor Min Dongchao was young during the turbulent years of the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976). Most of China’s schools and universities were closed down during that period, and the youth were sent to the countryside or to factories to learn from the working class. Professor Min spent the Cultural Revolution as a worker at the Tianjin Machinery and Tool Factory, beginning her factory career at the age of 15 in 1969 and staying there for eight years.

“During the Cultural Revolution, society was turned upside down. We grew up in a transformed environment with no language to talk about gender or differences between the sexes, because there wasn’t supposed to be any difference. Everybody wore the same kinds of clothes, did the same job, got the same pay, and so forth. There was basically no sexual division in society —at least not on the surface,”says Professor Min Dongchao.

The open door

It was only after the death of Mao Zedong in 1976 that schools and universities reopened, and it became possible for at least some of the so-called “sent down youth”to return to the education system. Once again, society was turned upside down: Foreign cultures and influences entered the country, spurring an irreversible development of Chinese society.

“Suddenly we could watch films and television from abroad, films that often demonstrated a clear gender differentiation, where men looked like men and women looked like women. So we wanted to look good, and we wanted to look different from men. Women started wearing makeup, and clothes in general became more colorful. Suddenly, a more diverse expression and mode of behavior were allowed again,”explains Min.

But there was another side to the new developments. It soon became more difficult for women to find employment, and they were paid gradually less, as men were generally favored in job situations. The factories started to lay off workers, and women were often the first to go. Other problems such as prostitution and men taking second wives also resurfaced and, according to Professor Min, this laid some of the foundation for why women and gender studies started taking off in China in the 1980s.

Professor Min returned to China in 2004 after almost ten years in the UK, and discovered a country in rapid transition. The new generations of young girls had reversed the Cultural Revolutionary tradition of going to the countryside. Instead, they were heading to coastal cities to work in factories —a mixed experience, to most. On the one hand, they experience the freedom of getting their own job, earning their own money, and freeing themselves from the pressure of country life. On the other, they work under exploitative conditions, are paid very little, and without any unions to protect them.

The introduction of gender

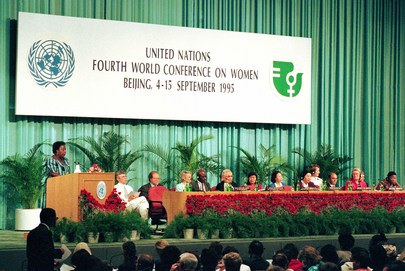

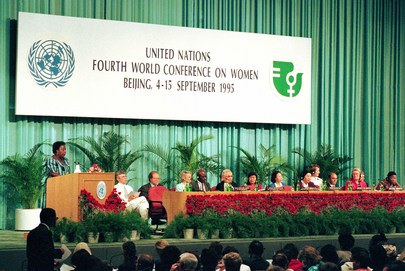

United Nations Fourth World Conference on Women Opens in Beijing, September 1995.

Gender as a concept was introduced into China in connection with preparations for the Fourth UN World Conference on Women, which was held in Beijing in 1995. There was growing awareness of increasingly visible gender inequality, and a new conceptual language to discuss these issues was made available to concerned academics and activists.

One of the gender-related issues under discussion in recent years is quotas. During the Mao era, the sex ratio was 50-50 in most party and government organs. In 2008, the government introduced gender quotas stipulating that 22% of the congress should be female, and last year, in collaboration with the All-China Women’s Federation, it was decided that there should be at least one woman on village committees. Professor Min, however, argues that the solution to gender inequality issues doesn’t lie only in quotas or the recognition of gender issues. Rather, it is a matter of general inequality in society at large:

“Gender equality should be addressed as a very important issue, and by this I don’t just mean gender difference —it is not a matter of achieving complete similarity between the sexes. Gender inequality has to do with general inequality in the society at large, the gap between rich and poor, inequality between the regions, between city and countryside. There are males and females of all classes and walks of life, so there are very rich females and very poor males. Gender inequality exists and can only be understood in the context of all levels of society, and within all classes. The inequality gap in general is growing bigger, which in turn affects gender inequality. When you conduct your research you may forget this, you may think in different categories, but you always have to see the society as a whole. The conditions for life in China are so dependent on geography and class. In many rural places, there are no proper schools, and children run around hungry. And then you have Shanghai with its multimillionaires —even billionaires. If you only look at one class or one geographic location, you get a skewed picture of what is actually going on in China,”Professor Min emphasizes.

The local is not subordinate to the global

Many academics agree that you cannot separate globalization and the local; they are two sides of the same coin. In other words, you cannot take the local out of the global. Globalization happens in the local. Professor Min argues that this is the case even for places with myriad global connections, like London: Even though all the money flowing through the financial center influences London from abroad, there is still a feature of something “local.”Understanding the global in relation to the local is a way to give prominence to people, because they are the ones who experience the changes on an everyday basis, and they are the ones who actually “practice”globalization.

As Professor Min notes, “We often see the railway as a symbol of globalization, because it links places together, but what we tend to forget is that there are places and people in between the stations. As with railways, there are different routes for gender studies in China. Some people go to Beijing and Shanghai and read Judith Butler, and then others go to the poor areas, like Yunnan. In Yunnan they have gradually changed the gender discourse and related practice, and as a result, the Yunnan Province Women’s Federation has managed to obtain more funding for larger projects than they have in places where they have not yet incorporated the new discourse.”

“Yunnan Province Women’s federation is a good example of how the global and the local are linked, of how things change in a local environment,”she argues.

The next generation

Female students protest gender quotas at Guangzhou University.

The new generation of women has begun to stir up radical performances and protests in the big cities. One example is a domestic violence protest last year in which young women painted their faces so it looked like they’d been beaten, and posted pictures of it on the Internet. Another incident was the Occupy Toilet Movement, where women occupied men’s rooms to protest the lack of women’s toilets in most public places.

“They might have gotten the idea from Taiwan or Hong Kong,”Professor Min adds.

Last year, some universities refused female applicants even though they had the same scores as their male counterparts. The Ministry proclaimed that for the sake of the country the universities needed more men, not girls. The women reacted by staging a happening where they shaved their heads and stood out on the street in defiance.

“Because of the Internet, this protest became a big deal. I think it’s good that young women have started to react to society’s gender inequalities; it is a good sign. I think it’s important that they protest, that they fight for something. My generation is about to retire, and we need the younger generation to take over and do the job. I hope that is what we’re seeing now,”Professor Min concludes.

Professor Min Dongchao, director of the Centre for Gender and Culture Studies at Shanghai University, has received the Marie Curie Actions International Incoming Fellowship and will be a guest professor at Nordic Institute of Asian Studies (NIAS) at the University of Copenhagen from April 1, 2013 to March 31, 2015.

Professor Min’s project is titled “Cross-Cultural Encounters —The Travels of Gender Theory and Practice to China and the Nordic Countries,”and is concerned with the cross-cultural translation of knowledge and practices that may or may not take place when different cultures interact, and the resulting production of new knowledge. Taking the travelling routes of gender theory and practices to, and also between, China and the Nordic countries as the empirical object of study, the project will focus on the crucial questions of why and how knowledge travels or fails to travel.

The open door

It was only after the death of Mao Zedong in 1976 that schools and universities reopened, and it became possible for at least some of the so-called “sent down youth”to return to the education system. Once again, society was turned upside down: Foreign cultures and influences entered the country, spurring an irreversible development of Chinese society.

“Suddenly we could watch films and television from abroad, films that often demonstrated a clear gender differentiation, where men looked like men and women looked like women. So we wanted to look good, and we wanted to look different from men. Women started wearing makeup, and clothes in general became more colorful. Suddenly, a more diverse expression and mode of behavior were allowed again,”explains Min.

But there was another side to the new developments. It soon became more difficult for women to find employment, and they were paid gradually less, as men were generally favored in job situations. The factories started to lay off workers, and women were often the first to go. Other problems such as prostitution and men taking second wives also resurfaced and, according to Professor Min, this laid some of the foundation for why women and gender studies started taking off in China in the 1980s.

Professor Min returned to China in 2004 after almost ten years in the UK, and discovered a country in rapid transition. The new generations of young girls had reversed the Cultural Revolutionary tradition of going to the countryside. Instead, they were heading to coastal cities to work in factories —a mixed experience, to most. On the one hand, they experience the freedom of getting their own job, earning their own money, and freeing themselves from the pressure of country life. On the other, they work under exploitative conditions, are paid very little, and without any unions to protect them.

The introduction of gender

United Nations Fourth World Conference on Women Opens in Beijing, September 1995.

Gender as a concept was introduced into China in connection with preparations for the Fourth UN World Conference on Women, which was held in Beijing in 1995. There was growing awareness of increasingly visible gender inequality, and a new conceptual language to discuss these issues was made available to concerned academics and activists.

One of the gender-related issues under discussion in recent years is quotas. During the Mao era, the sex ratio was 50-50 in most party and government organs. In 2008, the government introduced gender quotas stipulating that 22% of the congress should be female, and last year, in collaboration with the All-China Women’s Federation, it was decided that there should be at least one woman on village committees. Professor Min, however, argues that the solution to gender inequality issues doesn’t lie only in quotas or the recognition of gender issues. Rather, it is a matter of general inequality in society at large:

“Gender equality should be addressed as a very important issue, and by this I don’t just mean gender difference —it is not a matter of achieving complete similarity between the sexes. Gender inequality has to do with general inequality in the society at large, the gap between rich and poor, inequality between the regions, between city and countryside. There are males and females of all classes and walks of life, so there are very rich females and very poor males. Gender inequality exists and can only be understood in the context of all levels of society, and within all classes. The inequality gap in general is growing bigger, which in turn affects gender inequality. When you conduct your research you may forget this, you may think in different categories, but you always have to see the society as a whole. The conditions for life in China are so dependent on geography and class. In many rural places, there are no proper schools, and children run around hungry. And then you have Shanghai with its multimillionaires —even billionaires. If you only look at one class or one geographic location, you get a skewed picture of what is actually going on in China,”Professor Min emphasizes.

The local is not subordinate to the global

Many academics agree that you cannot separate globalization and the local; they are two sides of the same coin. In other words, you cannot take the local out of the global. Globalization happens in the local. Professor Min argues that this is the case even for places with myriad global connections, like London: Even though all the money flowing through the financial center influences London from abroad, there is still a feature of something “local.”Understanding the global in relation to the local is a way to give prominence to people, because they are the ones who experience the changes on an everyday basis, and they are the ones who actually “practice”globalization.

As Professor Min notes, “We often see the railway as a symbol of globalization, because it links places together, but what we tend to forget is that there are places and people in between the stations. As with railways, there are different routes for gender studies in China. Some people go to Beijing and Shanghai and read Judith Butler, and then others go to the poor areas, like Yunnan. In Yunnan they have gradually changed the gender discourse and related practice, and as a result, the Yunnan Province Women’s Federation has managed to obtain more funding for larger projects than they have in places where they have not yet incorporated the new discourse.”

“Yunnan Province Women’s federation is a good example of how the global and the local are linked, of how things change in a local environment,”she argues.

The next generation

Female students protest gender quotas at Guangzhou University.

The new generation of women has begun to stir up radical performances and protests in the big cities. One example is a domestic violence protest last year in which young women painted their faces so it looked like they’d been beaten, and posted pictures of it on the Internet. Another incident was the Occupy Toilet Movement, where women occupied men’s rooms to protest the lack of women’s toilets in most public places.

“They might have gotten the idea from Taiwan or Hong Kong,”Professor Min adds.

Last year, some universities refused female applicants even though they had the same scores as their male counterparts. The Ministry proclaimed that for the sake of the country the universities needed more men, not girls. The women reacted by staging a happening where they shaved their heads and stood out on the street in defiance.

“Because of the Internet, this protest became a big deal. I think it’s good that young women have started to react to society’s gender inequalities; it is a good sign. I think it’s important that they protest, that they fight for something. My generation is about to retire, and we need the younger generation to take over and do the job. I hope that is what we’re seeing now,”Professor Min concludes.

Professor Min Dongchao, director of the Centre for Gender and Culture Studies at Shanghai University, has received the Marie Curie Actions International Incoming Fellowship and will be a guest professor at Nordic Institute of Asian Studies (NIAS) at the University of Copenhagen from April 1, 2013 to March 31, 2015.

Professor Min’s project is titled “Cross-Cultural Encounters —The Travels of Gender Theory and Practice to China and the Nordic Countries,”and is concerned with the cross-cultural translation of knowledge and practices that may or may not take place when different cultures interact, and the resulting production of new knowledge. Taking the travelling routes of gender theory and practices to, and also between, China and the Nordic countries as the empirical object of study, the project will focus on the crucial questions of why and how knowledge travels or fails to travel.

闵冬潮教授即将在哥本哈根大学北欧亚洲研究所(NIAS)开展为期两年的研究工作,她研究的题目是:“Cross-Cultural Encounters — The Travels of Gender Theory and Practice to China and the Nordic Countries,”。该项目获得欧盟玛丽·居里行动计划国际人才奖学金的资助。

本文版权为文章原作者所有,转发请注明本网站链接:http://www.cul-studies.com